Along the coastline of the northern Olympic Peninsula, a relatively obscure rodent has been burrowing out an existence beneath stands of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) for centuries. Known commonly as “mountain beaver,” no relation to the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis), has been called many names, notably boomer, ground bear, giant mole, or sewellel beaver.

Despite its prominence on the peninsula, the creature remains relatively unknown to people living outside our region. In fact, few people have ever heard about the medium-sized rodent, which looks similar to a tailless muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), much less seen one. A case in point: once I mentioned to out-of-town friends a mountain beaver was stealing leeks from my garden. I was met with dazed expressions and the obligatory question, “What’s a mountain beaver?”

The primitive—not prominent—rodent

The most primitive family of rodents, Aplodontiadae, dates back to the Miocene Epoch (23.03 to 5.332 million years ago). Aplodontiadae is now comprised solely of one genus, Aplodontia to which the mountain beaver species (Aplodontia rufa) remains the only living member.

Mountain beavers are endemic to North America and exist in a limited range along the Pacific Coast. Explorers Lewis and Clark first recorded observing the animal on February 26, 1806, at Fort Clatsop, Oregon. At present, there are seven recognized subspecies. Their entire range extends from southern British Columbia, west of the Cascade Mountains to northern California. However, populations are most abundant in the coastal Olympic Mountains and in the coast range of Washington and Oregon. On the Olympic Peninsula, the subspecies, Aplodontia rufa rufa, so named by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1817, can be found often in earthen hillsides, but seems to thrive in the vegetated bluffs along the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Unlike a handful of other regional rodents such as the Olympic marmot (Marmota olympus), and Townsend’s chipmunk (Neotamias townsendii), mountain beavers remain active year round; thus, they do not hibernate.

Though mountain beaver populations are not geographically extensive, their ecological impact is significant enough that ecologists have categorized them as a keystone species—a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance. The mountain beaver, along with some other species (the sea otter [Enhydra lutris], for example), affects many other organisms in an ecosystem, thus directly influencing the types and numbers of various species in the community.

Let’s get physical

The average adult mountain beaver is grayish or reddish brown in color and weighs a little over 2 pounds; however, its stout body may weigh from 1 to 4 pounds. The animal’s average overall length is 13.5 inches, including a stubby, 1-inch-long tail. One of the mountain beaver’s key characteristics is a single pair of constantly-growing incisor teeth specialized for gnawing shrubs and trees. Their eyes and ears are rather small, illustrative of their poor eyesight and hearing. However, they possess a keen sense of smell and touch, ideal for their mostly subterranean lifestyle. They use their long whiskers (see below: “Boomers don’t always burrow”) as feelers, which offer a fine counterbalance to their poor vision. The animal’s front feet are designed for grasping and climbing; slightly shorter than its 2-inch-long hind feet. Both front and back feet sport long, slender toes (Figure 1).

Dig it. The burrow system

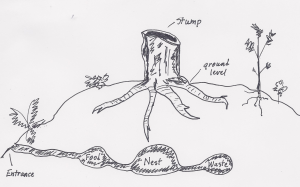

Mountain beavers are known for their elaborate, well-organized burrow systems that they deftly compartmentalize to accommodate nesting, food stores, and fecal deposits (Figure 2).

Some 10 to 30 open exits may be found along the complex tunneling system comprised of a main burrow joined by several T‑shaped junctions. Burrows are commonly found under old logs, tree stumps or other vegetative debris (Figure 3).

The nesting area within the burrow system is a dome-shaped cavity, typically 3-4 feet below ground level. Its size varies, but commonly extends to about 2 feet wide and 1 to 2 feet high. Mountain beavers are quite skilled as earthen architects. They use their front feet to pack soil against the dome, which then becomes a hardened, protective shell.

These animals are primarily active at night. When observed during daytime hours, they are usually partially concealed in areas of heavy vegetation where they gather plants to take back to their burrows. Mountain beavers are not social, though in some areas on the Olympic Peninsula populations are dense, and burrowing systems can be close, often overlapping on the same hillsides. Because they are solitary animals, except during breeding, a mountain beaver will defend her system against trespassing neighbors. However, when she vacates her burrow or dies, the system is often quickly reoccupied by another mountain beaver. Also, those same vacated tunnels become the playground for mice, moles, voles, rats, cottontail rabbits (genus Sylvilagus), long-tailed weasels (Mustela frenata), spotted skunks, and a host of other local denizens.

Chew on this. The mountain beaver diet

Mountain beavers have inefficient kidneys and, thus do not produce concentrated urine. They must supply one-third of their body weight in water every day, which they acquire solely from the vegetation they eat.

Fleshy herbs and young shoots of woody plants are the mountain beaver’s primary food source. Sword fern (Polystichum munitum) and bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) are particular favorites. Also, they climb shrubs and small trees to gnaw off branches. They can chew off stems as thick as ¾ to 1 inch. Since Douglas fir, hemlock, western red cedar (Thuja plicata), and red alder (Alnus rubra) are within their primary habitat, mountain beavers frequently cut and eat these available tree species. They have a common habit of storing food at the entrances to their burrows, known as “haystacking.” At certain times of the year, it is not unusual to see large piles of fern fronds or other cut vegetation at burrow openings.

When above ground, the animals usually feed close to their burrows (within 50 feet), but will occasionally wander several hundred feet. From personal observation, I have watched lone mountain beavers move across wide open spaces as they travel from one highly-vegetated area to another.

Mountain beavers are hindgut fermenters, which, like rabbits and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus), means they practice coprophagy (the eating of feces) whereby they consume partially-digested fecal pellets (first pass) to obtain adequate nutrients. After re-ingesting these nutrients, they drop hard fecal matter (second pass), which they then transfer to dedicated fecal chambers within the burrow (see Figure 2).

And speaking of food, mountain beavers are top fare for many local predators. Bobcats (Felis rufus), coyotes (Canis latrans), cougars (Puma concolor) and great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) are just a few common predators. On the Olympic Peninsula, long-tailed weasels also can be a nuisance. Weasels are not only fearless and aggressive, but able to access mountain beaver burrows with their sleek body configuration and speed. That being said, weasels typically prey mostly on the young who may be left unattended in the burrow.

A solitary life…except…

Mountain beavers lead solitary lives with one exception—breeding season—which extends from January to March. Gestation lasts about 30 days. Two to three young are born blind and hairless, weighing about 3/4 ounces each. They develop incisors at about 30 days and are weaned at eight weeks. Young animals are often active in May-June. The animal’s lifespan can be anywhere from five to 10 years.

Relative to some of their relatives, mountain beavers remain relatively free of diseases and internal parasites. A species of flea (Hystrichopsylla schefferi), unique to the mountain beaver, is the largest flea known to modern science. Females of this flea can grow to be 0.5 inches long, but the flea has never presented a problem for humans.

Damaged goods

Mountain beavers are known to cause considerable damage to forested areas on the Olympic Peninsula and can contribute greatly to erosion problems when they undercut banks and hillsides with extensive tunneling. The common and costly problem is their cutting of planted tree seedlings that can result in large areas not being adequately reforested. For example, a planned 40-year rotation of Douglas-fir crop can be severely affected if mountain beaver activity causes significant damage to the crop at 15 years.

For an average property owner, mountain beavers create an ongoing nuisance in gardens and embankments where they dig holes, gnaw off trees, and often undermine the root systems of establishing vegetation. Their presence leads to erosion problems that are difficult to overcome with continued destructive activity.

Given their uncanny ability to survive essentially unchanged for millions of years, Aplodontia rufa rufa may turn out to be the last rodent standing. Friend or foe, mountain beavers continue to fascinate the people who actually know about them. If you are lucky enough to observe one in the wild, enjoy the experience as you keep something in mind. You’ve just seen an animal that, to the vast majority of the world, doesn’t even exist.

Boomers don’t always burrow…

One spring morning, my husband went to the storage area under our house to retrieve the lawnmower. As he approached, he heard movement and, shortly, what sounded like a sizable animal ambling toward the corner furnace. It was too dark to get a visual, though the possibilities were many. A rat, squirrel, weasel, skunk…

Thinking the animal would return, he made note of the critter’s escape route, then turned out the light and left. A couple hours later, my husband came back armed with a Havahart® small animal trap, which he quietly and carefully placed (spring loaded for capture) in line with the critter’s path of escape.

Then came the moment of truth. He gave the lawnmower a firm jiggle. Sure enough, the intruder again made his move for the exit…and right into the trap.

Outside, the mystery intruder was revealed. A very surprised mountain beaver! We named him Boomer and made plans to release him a considerable distance from the house.

The lawnmower held Boomer’s long winter secret. Inside the grass-catcher, he had constructed for himself a plush little home. Dark, dry and safe from predators, no doubt he had planned to stay a while.

“Boomer” (top) enjoys a fresh leek prior to his release back into the wild. Grass-catcher (below) in which Boomer had constructed quite a plush home for himself. Unfortunately, his lease was short term and he was ceremoniously evicted.

Sources

Phillipsen, Ivan. “Wild Pacific Northwest.” http://www.wildpnw.com/2010/11/14/how-animals-survive-the-winter-in-northwest-mountains/ (Accessed 04/24/2012)

Link, Russell. “Living with Wildlife.” Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, http://wdfw.wa.gov/living/book/ (Accessed 04/21/2012)

Steele, Dale T. “The Mountain Beaver Journal.” http://web.me.com/dtsteele/Mountain_Beaver_Work/index.html (Accessed 04/22/2012)

Campbell, Dan. “Mountain Beavers.” Denver Wildlife Research Center, http://www.icwdm.org/handbook/rodents/ro_b53.pdf (Accessed 04/21/2012)

Ostrom, Carol M. “The Pacific Northwest’s Elusive Mountain Beaver.” Seattle Times, Sunday, February 8, 2009. (Accessed 04/25/2012)

National Geographic.com. http://www.nationalgeographic.com/lewisandclark/record_species_048_15_11.html (Accessed 04/27/2012)